By Dee Jae Cox

The heat was oppressive, bearing down like a weight, as the humidity caused the clothes to cling to the skin like a wet sheet. It was just another summer day when General Gordon Granger and 2,000 Union troops rode horseback into the port city of Galveston Texas on June 19, 1865. The Civil War had ended two months earlier on April 9th, when General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Confederated troops to Union General Ulysses S. Grant in Virginia. President Lincoln had given a speech on April 11th, promoting voting rights for black men, this is what had incited actor and Confederate Spy, John Wilkes Booth, to violently retaliate. Four days later, Booth assassinated Lincoln, leaving a broken country in the aftermath of devastation.

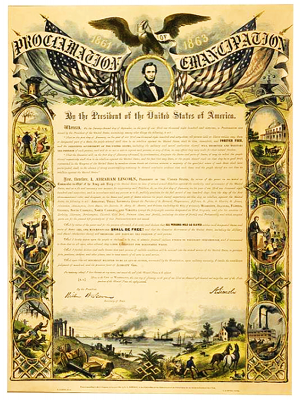

In the days prior to the internet, television and even radio, news was slow to spread. The losing Confederate soldiers were not eager to share the story of their loss or what this meant to the hundreds of thousands of enslaved men and women. The returning Confederates therefore said nothing of the Emancipation Proclamation, which had freed enslaved people in the South in 1863. The Proclamation could not be enforced in many places until after the end of the Civil War in 1865. Heralded as the savior of the Union, President Lincoln, actually considered the Emancipation Proclamation to be the most important aspect of his legacy. “I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right, than I do in signing this paper,” he declared. “If my name ever goes into history it will be for this act, and my whole soul is in it.”

Two years later, at the conclusion of the war, the slaves in Texas knew nothing of Lincoln’s great legacy, the Emancipation Proclamation, or even that the North had won the war and they were free. When Granger and the Union Army rode in to Galveston, it came as a complete shock to the enslaved people, when he delivered General Order No. 3, which said: “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.”

It would be six months later in December of 1865 when the 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution was passed, abolishing slavery as an institution in all U.S. States and territories and outlawing the practice of involuntary servitude, (forcing someone to work in service in order to pay off a debt.) But on that hot summer Texas day in June 1865, when the army announced that the more than 250,000 enslaved black people in the state, were free by executive decree, it was a shock that still reverberates to this day.

June 19th came to be known as “Juneteenth,” America’s second Independence Day. The next year, the now-free people started celebrating Juneteenth in Galveston and its observance has continued around the nation and the world ever since.

The post-emancipation period known as Reconstruction, (1865-1877) marked an era of great uncertainty and struggle for the nation. Forty Acres and a Mule, was part of Special Field Orders No. 15, a wartime order proclaimed by Union General William Sherman. On January 16, 1865, as an offer of restitution, it was agreed to allocate land to freed families. They would be given plots of land, no larger than 40 acres and the army would lend mules towards the effort.

Section one of the Order states: “The islands from Charleston, south, the abandoned rice fields along the rivers for thirty miles back from the sea, and the country bordering the St. Johns River, Florida, are reserved and set apart for the settlement of the negroes [sic] now made free by the acts of war and the proclamation of the President of the United States.”

Unfortunately, after Lincoln was assassinated, Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s successor and a sympathizer with the South, overturned the Order in the fall of 1865, and as historian Barton Myers stated, “returned the land along the South Carolina, Georgia and Florida coasts to the planters who had originally owned it” — to the very people who had declared war on the United States of America. Restitution is still pending.

Opal Lee, a 95-year-old retired teacher from Marshall, Texas has become known as the Grandmother of Juneteenth. On June 19th, 1939, when Lee was 12 years old, a mob of white rioters burned down her family’s home. Years later, she said, “The fact that it happened on the 19th day of June has spurred me to make people understand that Juneteenth is not just a festival.” Lee, campaigned for decades to make Juneteenth a federal holiday. She promoted the idea by leading 2.5 mile walks each year, representing the 2.5 years it took for news of the Emancipation Proclamation to reach Texas. She promoted a petition for a Juneteenth federal holiday which received 1.6 million signatures. She said, “It’s going to be a national holiday, I have no doubt about it. My point is let’s make it a holiday in my lifetime.”

In June 2021, at the age of 94, her efforts succeeded as a bill to make Juneteenth a federal holiday was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Joe Biden. Ms. Opal Lee, was an honored guest at the bill signing ceremony and received a standing ovation.

In June 2021, at the age of 94, her efforts succeeded as a bill to make Juneteenth a federal holiday was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Joe Biden. Ms. Opal Lee, was an honored guest at the bill signing ceremony and received a standing ovation.

There are those who would sometimes choose to erase history rather than honor it. Slavery is a thread in the fabric of the American culture, that cannot be removed without unraveling all that we have overcome and hope to be. Philosopher George Santayana, The Life of Reason, 1905, stated, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Banning books or refusing to educate children about slavery, will not alter the truth of American history.

Dee Jae Cox, is a playwright, director and producer.

She is the Cofounder and Artistic Director of The Los Angeles Women’s Theatre Project

www.losangeleswomenstheatreproject.org

And Co-Creator of the Palm Springs Theatre Go-To Guide,