By Eleni P. Austin

I don’t know about you, but for me, there is nothing better than listening to the (seeming) effortless and achingly pure sound of familial harmonies. I find it positively thrilling. It’s not just music you hear, it’s music you feel. As a kid, I was drawn to The Osmonds, The Everly Brothers The Beach Boys and The Andrew Sisters. As I got older, it’s what I loved about The Roches, Sweethearts Of The Rodeo and The Williams Brothers.

Identical twins Andrew and David Williams grew up in a showbiz family. Their dad Don, along with brothers Robert, Dick and Andy, began performing as The Williams Brothers in the late ‘30s. The quartet performed with both Bing Crosby and Kay Thompson before Andy embarked on a solo career. Signature songs like “The Days Of Wine And Roses,” “Moon River” and “Can’t Get Used To Losing You,” skyrocketed him to fame in the ‘50s and early ‘60s. He hosted his own weekly TV variety show from 1962 to 1971.

As kids, Andrew and David had their minds blown by The Beatles. They began harmonizing at an early age and appeared, along with the rest of the Williams clan, on Uncle Andy’s annual TV Christmas specials. As soon as adolescence hit, they began receiving fan mail. Soon enough, they were signed to a record label, marketed as teen idols and were feted in august publications like 16, Tiger Beat and Spec (don’t roll your eyes I religiously read all three in the early ‘70s). An appearance on The Partridge Family cemented their burgeoning fame. They didn’t really have that much say in what they were recording, but they happily went along for the ride. When their popularity waned, they returned to their normal lives and began creating their own music.

By the early ‘80s they were popping up on albums by T-Bone Burnett and The Plimsouls, and playing all the usual L.A. clubs. The cognoscenti noticed, and within a couple of years, they signed a record deal with Warner Brothers. Their debut, Two Stories, arrived in 1987, awash in gossamer harmonies, deft arrangements and jangly instrumentation. Produced in part by Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers guitarist, Mike Campbell, his participation raised their profiles considerably. Although the brothers’ sharp compositions dominated the album, it also included unreleased songs by Bob Dylan, Stevie Nicks and Tom Petty.

Four years later they recorded their self-titled, sophomore effort. A watershed record, it felt more Rootsy and intimate and contained the heartfelt ballad “Can’t Cry Hard Enough,” written by David and their pal, Marvin Etzioni. A bona fide hit, it climbed to #42 on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart. Their third album, Harmony Hotel was released in 1993. A quietly confident collection of 10 songs, it included “Don’t Look Now,” a heartbreaking commentary on the AIDS crisis, the tender “Where Would I Be” and the rollicking “Wonderful Blues.”

By this time the brothers had opened for everyone from Roy Orbison and Suzanne Vega, to the BoDeans, Victoria Williams (no relation), and even Linda Ronstadt. Indie film director Allison Anders had tapped them to play a brotherly singing act in her Brill Building/Beach Boys roman a’ clef, Grace Of My Heart. But Andrew and David, both ready for new challenges, opted to go their separate ways professionally. Andrew has gone on to become an in-demand record producer and David focused on his passion for architecture, interior and landscape design.

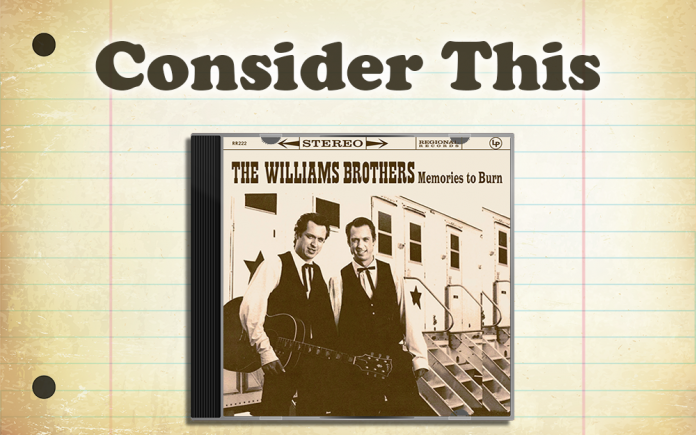

Around the same time the brothers had parted ways with their record label and began filming Grace Of My Heart, their pal, Marvin Etzioni suggested they make a Country-flavored album. It was a very spontaneous affair, they cobbled together a set-list of songs that spoke to them. Marvin played bass and produced, he also enlisted Greg Leisz on pedal steel and Don Heffington on drums. Andrew pushed the “record” button. Since the guys were exploring divergent career paths, the tapes were filed away. Marvin is probably best known as bass player for Lone Justice, but he’s also a protean singer-songwriter who launched a solo career in the early ‘90s, as well as a multi-instrumentalist and producer. In the early days of the pandemic, he had signed a digital distribution deal with Six Degrees for his label, Regional Records. That prompted him to call Andrew and find out what happened to those live to 2-track recordings. They were still on a shelf. Once Marvin received the files via email, he went through and edited. Andrew mixed and engineered, and then it was mastered by Sean Magee at Abbey Road. The result is Memories To Burn, a 10-song set recorded over 25 years ago that is finally seeing the light of day.

The album opens with a crackling version of “Tears Only Run One Way,” One of two songs they tackle by sardonic alt.country Rocker, Robbie Fulks. Andrew and David’s close harmonies perfectly coalesce atop weepy pedal steel, a rippling backbeat, descending, slap-back bass lines and plucky acoustic guitar. Lachrymose lyrics sing the Blues on this sad-sack saga of love gone wrong; “Our love ran wild, it took us higher than the sky, man it was a real ride, we kissed, we fought, yeah, we ran cold and hot, but there’s no two ways about the way I feel right now.” Despite the romantic sturm und drang, the blithe arrangement and fluttery pedal steel adds a layer of Grand ole Opry verisimilitude.

Marvin’s original songs are afforded the most bandwidth, beginning with “Cryin’ And Lyin’.” Chugging acoustic guitars partner with swoony pedal steel, bucolic bass and a clanky, propulsive beat on this twangy Texas Two-Step. Essentially, they can’t go on together with suspicious minds; “Don’t tell me that your hair is messed up for no reason, even your mascara is leavin’ what am I to believe, you’re so close but out of reach.” Piquant pedal steel hugs the melody’s hairpin curves, mirroring the rollercoaster of emotions.

The defiant “You Can’t Hurt Me” is powered by chunka-chunka rhythm guitar riffs, bristling bass lines, insolent pedal steel notes and a see-saw beat. Andrew and David’s symbiotic harmonies wrap around lyrics that close the door on a failing romance; “I won’t take the blame, for the pain you’re in, I’m not a faceless name, I’m not a shot of gin.” Prickly pedal steel is matched by slinky acoustic licks on the beak, adding just a soupcon of Everlyesque flavor.

On the title track, hiccoughing harmonies, darting pedal steel, jangly guitars, and quarter tone bass lines are tethered to a finger-poppin’ beat. An intriguing cri de Coeur, it manages to reference a Paul Simon deep cut, “How The Heart Approaches What It Yearns,” as the lyrics articulate the feelings of ambivalence that accompany a break-up; “What am I supposed to do, with all of these pictures of you? What am I supposed to do, I got memories to burn/I’m gonna throw it all in the fire, watch the flames go higher and higher, it’s a beautiful sight, I wish you were here tonight.”

By “Unanswered Prayers,” all the equivocation has receded. Liquid guitar arpeggios line up with keening pedal steel, thrumming bass and a barely-there beat. Rather than set the world on fire, the lyrics kind of wallow in the mire, before looking to a higher power; “Night after night I was lonely, thinking ‘bout you only, why, baby why, did you hurt me so bad, I ain’t never, I ain’t never been so sad/Thank God for unanswered prayers, Thank God for being there, cause if they all came true, I would still be with you,”

Since this was something of a busman’s holiday for Andrew and David, the album only features one of their own original compositions; “She’s Got That Look In Her Eyes.” The track is in line with the record’s themes of sin, salvation and sorrow. Equal parts Torch and Twang, hushed harmonies feather atop mournful pedal steel, ringing guitars, wily bass and a tick-tock beat. Lyrics limn the sting of betrayal; “She’s got that look in her eyes, it’s not hard to tell, I know she’s biding her time to say farewell, she’s got that look in her eye, I know she’s saying goodbye, she could never lie too well.”

The best songs here ricochet from the sacred to the profane, with a brief, but bittersweet detour in-between. First up is Iris DeMent’s glorious “Let The Mystery Be.” Rip-snortin’ guitar riffs ride roughshod over sly pedal steel, agile bass lines and a simpatico shuffle rhythm. Clear-eyed lyrics attempt to define the temporal world and the hereafter; Some say they’re goin’ to a place called Glory and I ain’t saying it ain’t a fact, but I’ve heard that I’m on the road to purgatory and I don’t like the sound of that, well, I believe in love and I live my life accordingly, I think I’ll just let the mystery be.”

“Death Of A Clown” is their take on the classic Kinks jeremiad. The original had a wheezy, Music Hall lilt. But Andrew, David and Marvin deconstruct the arrangement, paring it down to a bare-bones, backwoods lament. Shivery pedal steel lattices strummy guitars, woebegone bass and a sturdy beat. Lyrics paint a grim portrait of life under the big top, that reflects the gritty existence of a road-weary musician; “My makeup is dry and it cracks ‘round my chin, I’m drowning my sorrows in whisky and gin, the lion tamer’s whip doesn’t crack anymore, the lions, they won’t bite, the tigers won’t roar/The fortune teller lies dead on the floor, nobody needs fortunes told anymore, The trainer of insects is crouched on his knees, and frantically looking for runaway fleas.” The brothers’ soaring and ethereal blend keeps the song from becoming too maudlin. (And for the record, someone needs to recalibrate a klutch of Kinks kuts, adding a kountry-tinge. What? Okay, I’ll kwit).

Finally, their second Robbie Fulks cover, “She Took A Lot Of Pills (And Died)” lands somewhere between Loretta Lynn’s “Your Squaw Is On The Warpath” and Nick Lowe’s “Marie Provost.” Barbed pedal steel, shimmery guitar and brittle bass connect with a thumping beat. The lyrics offers up an evocative narrative worthy of novelist Nathanael West; “At 20 years old, she was as rich as she could be, and a world-famed Hollywood star.” Of course, fame is fleeting; “While the traffic crawled by in the street outside, she was sitting in her kitchenette, listening to the scuttle of the rats in the wall, and staring at her TV set/She once might have been too proud to be found in a hovel on the lower East Side, but nothing in the world seemed to matter much now, so she took a lot pills and died.”

The record closes with a tender take of Buffy Sainte-Marie’s “The Piney Wood Hills.” The brothers’ harmonic alchemy is front and center, bookended by cascading acoustic riffs, melancholy pedal steel, dolorous bass and a waltzing ¾ beat. The ache is palpable as the song’s dusty travelers yearn to return home; “I’m a rambler and a rover, and a wanderer it seems, I’ve traveled all over, chasing after my dreams, but a dream should come true and a heart should be filled, and a life should be lived in the Piney Wood Hills.” It’s a sweetly apropos finish, to a wonderfully organic and timeless record.

The record closes with a tender take of Buffy Sainte-Marie’s “The Piney Wood Hills.” The brothers’ harmonic alchemy is front and center, bookended by cascading acoustic riffs, melancholy pedal steel, dolorous bass and a waltzing ¾ beat. The ache is palpable as the song’s dusty travelers yearn to return home; “I’m a rambler and a rover, and a wanderer it seems, I’ve traveled all over, chasing after my dreams, but a dream should come true and a heart should be filled, and a life should be lived in the Piney Wood Hills.” It’s a sweetly apropos finish, to a wonderfully organic and timeless record.

Memories To Burn echoes antecedents like The Everly Brothers and The Louvin Brothers. The lean and unfussy arrangements and instrumentation adroitly allow the spotlight to shine on Andrew and David’s fraternal blend.

Of course, for this fan, I want there to be more. New songs, live recordings or more unreleased music, I’m not picky (well, maybe no 12” dance remixes). But even if that never happens, at least there’s this gift. Or, as their pal, Louisiana native Victoria Williams might characterize it, this lagniappe. That’s a French-Cajun term that means “a little something extra.” Thanks to Marvin Etzioni, The Williams Brothers have given the world a little something extra, and for now, that will suffice.