By Heidi Simmons

“It wasn’t just in his black eyes, it was his whole energy,” said Jenifer Asbenson about the evil she experienced at the hands of her attacker. “It was so scary. I knew he was going to kill me.”

Serial killer Andrew Urdiales raped and murdered eight women before being apprehended. Asbenson was the fifth victim. She was 19 years old and the only woman to escape his deadly grasp.

“During the attack I stopped pleading for my life,” said Asbenson. “He was toying with me. Having hope that he would let me go felt like torture. Usually it’s good to have hope, but not in this case. It was the worst. With hope, I could feel everything he was doing to me. My life was in his hands and there was nothing to negotiate. It was pure evil — how evil is disguised on this planet. I wanted it to end. So I told him to just go ahead — shoot me.”

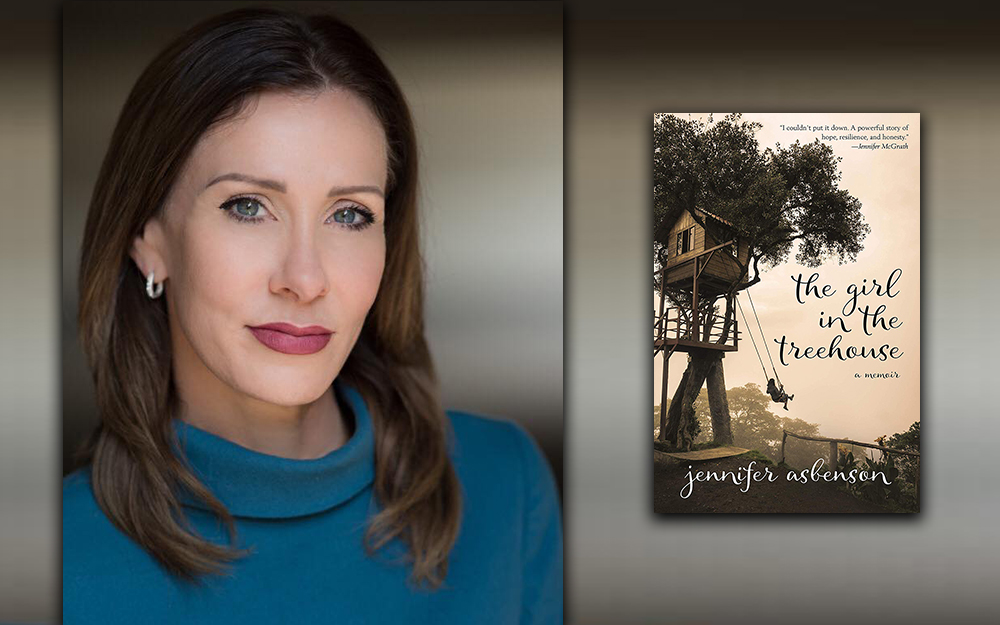

In her new book, The Girl in the Treehouse, Asbenson recounts her life growing up in and around the Coachella Valley with a dysfunctional family and the challenges that shaped her and gave her the strength to survive such intense trauma.

SACRED SPACE

Asbenson shared her story from the safety of her cozy, eclectic, split-level tree house – the inspiration for the book’s title.

Asbenson shared her story from the safety of her cozy, eclectic, split-level tree house – the inspiration for the book’s title.

“It’s like a womb,” Asbenson said about her beloved tree house and creative space. She birthed her book from the secure backyard location over two years — an extension cord, an umbilical, provides her sanctuary with power.

Converted from a boys’ fort, Asbenson meticulously curated the tree house interior.

“If you are afraid of the story you are about to tell, you keep finding projects to do,” said Asbenson. “I moved in here because I didn’t want any distractions. I knew the depth of what I was going into with every chapter. It could be a good ride or bad. I had to get the space right until there was nothing more to do but write.”

The tree house has a “bedroom” and a living space with a chair, daybed and coffee table. Fabric mandalas are draped over the ceiling and walls, Persian rugs cover the floors, soft lights illuminate the comfortable space; candles, incense and mellow music infuse a relaxed and easy atmosphere. She has red wine, water and snacks on a tray.

Asbenson’s tree house is not a child’s hideout any longer, but an adult’s peaceful refuge.

READY TO WRITE

Part of Asbenson’s routine before writing was to drink some wine and smoke some cannabis – a sativa – to relax and focus.

“I could write with total honesty, without any embarrassment and just be human,” said Asbenson. “I knew that if I am completely real, I’m going to be able to connect with somebody and help people.”

Asbenson sat in an under-sized floral armchair leaning in, now and again, using her hands to emphasize the trauma – revisiting the lessons she has learned about herself through the writing process.

“During the attack, I went into shock and it protected me from feeling anything,” said Asbenson. “Hope hurt. I went from the highest extreme to the lowest low. Believing he might set me free was not going to change his mind. I knew I wasn’t going to live. When I said ‘kill me,’ that surprised him and the situation changed. Once the evil was no longer right in my face, I got a chance to calm my mind.”

Asbenson talks about the abduction, confrontation and escape, with candor in The Girl in the Treehouse. (See CVW Book Review)

DEVINE INTERVENTION

The harrowing account includes what Asbenson believes was divine intervention.

The harrowing account includes what Asbenson believes was divine intervention.

Locked in the dark trunk of her abductor’s car, Asbenson prayed and light temporarily illuminated a small section where she managed to find the release latch and get out. Her abductor pursued her as she ran barefoot, injured and half naked through the desert.

“I am a spiritual person and believe in God,” said Asbenson. “To me, a prayer is a form of meditation; a way to calm yourself and think. I see a spiritual connection because I choose to. There’s so much we can’t answer. Did a hand turn the lock? Was it my imagination? Somehow, I knew exactly what to do. We try to think what makes sense to us. But, he put me in the trunk and that gave me an opportunity. The other women didn’t get that chance.”

When Asbenson was rescued and first responders came to help, her mother doubted her daughter’s story. Asbenson expected people would show her love, compassion, and provide her with help. It didn’t come. Her mother quipped, “It’s what you get for hitch-hiking.” The blame and betrayal further traumatized Asbenson.

For years after the abduction, Asbenson feared her attacker would come after her again. He had her driver’s license and purse she left in his car.

Some people disbelieved Asbenson’s story while others referred to her as “the kidnapped girl.” She was in and out of mental health facilities suffering from PTSD and other psychiatric challenges stemming from the attack. There was no professional therapeutic help provided to her for the horrific trauma. While confined and given a litany of medications, she questioned her own truth.

THE GIRL

Asbenson is tall, lean and very pretty. She exudes sweetness, sincerity and a childlike innocence that is beautiful. She giggles with ease. She’s thoughtful before answering questions. She’s happy. Although she appears fragile and vulnerable, there is strength, wisdom and conviction that radiates under the surface.

“I don’t think I would have been kidnapped, or survived if it wasn’t for my childhood,” said Asbenson. “Because of the way I was treated at home, I’d take risks and trust people. I had no self-esteem, self-respect or self-love. I was naïve.”

As a kid, Asbenson’s father built a geodesic dome on a remote parcel of desert land. She had a disabled little brother and her family struggled financially. They had no running water or electricity. She often went without food, shoes and new clothing. Her mother mentally and physically abused her.

“I didn’t write this book as someone who got away from a serial killer. If I wrote just about that, the story wouldn’t make sense. It’s about my life, which is all part of the complete picture.”

IDENTIFIED

When her attacker was caught in the Midwest, Asbenson was shown photos by the local Sheriff. She immediately identified Urdiales. She asked to talk with the other victims, but law enforcement revealed that the others were all deceased. She was the only one to survive.

“I was hoping to bond with the other women,” said Asbenson.

Asbenson has bonded with the other victims. She dedicated her book to them.

When Urdiales confessed, he named all his victims and told the police about a girl in California named Jennifer who escaped. Asbenson does not know why he chose to confess.

“He was caught with a gun that he used to kill a girl,” said Asbenson. “He could have denied it was his. But he didn’t.”

Urdiales was arrested in 1997.

Asbenson testified against her attacker in three different trials. The California trial was in 2018.

TESTIMONY

“I didn’t want him there during my testimony, but it’s his right to be present,” said Asbenson. “At first, I wanted to be a warrior and inspirational when I took the stand. Show him how strong I was. He didn’t kill me. I survived. But, when I looked at the Jury, I realized they needed to hear exactly what happened that day – back then – from the person I was, not who I am now. They had to hear how terrifying it was and what he did to me. It was daunting being in front of him.”

The attack was on September 28, 1992. Asbenson says it with unhesitating confidence the date permanently seared into her soul.

Asbenson suffered terrible PTSD nightmares and sleep paralysis. She read everything she could about letting go of resentment, bitterness and anger. All the advice recommended forgiveness, something Asbenson could not bring herself to do.

FORGIVENESS

“The families of the other victims and I spoke at the sentencing,” said Asbenson. “Up to that time, I had not forgiven him. But, in the moment, I did, and it was a relief. I was made of concrete and then I became light as a bird.”

“The families of the other victims and I spoke at the sentencing,” said Asbenson. “Up to that time, I had not forgiven him. But, in the moment, I did, and it was a relief. I was made of concrete and then I became light as a bird.”

Asbenson’s PTSD nightmares stopped.

“Forgiving someone isn’t about saying ‘What you did was okay,’” said Asbenson. “It’s about putting it behind you and saying ‘it’s not on me. It’s on you.’”

Asbenson went as far as to thank her attacker for letting her breathe. (He strangled her until she blacked out.) She went down a list of the things she was grateful for. According to Asbenson, none of the families were hostile toward the killer, but only spoke about the beauty and goodness of those they lost.

Urdiales was convicted and sentenced to death. He was transferred to San Quentin where he hanged himself a week later. Asbenson believes the evil inside his whole body turned on him.

“He couldn’t feed off our anger anymore,” Asbenson said.

Many family members of Urdiales’ victims have embraced Asbenson; one father feeling the spirit of his daughter living on in Asbenson. For her, “survivor’s guilt” has shaped itself into helping others.

WORTHY

“I wasn’t doing my best, I was self-destructive and using drugs,” said Asbenson. “Why am I here if I’m going to feel guilt about being alive. It’s a different kind of survival. I needed to feel worthy.”

Regarding the recent case of Jayme Closs who managed to escape her abductor Asbenson said, “She is going to need a lot of help. I hope she gets it.”

Other survivors have reached out to Asbenson. “I listen. I won’t give them advice. I only tell them the things that I’ve done. Or share what helped me,” said Asbenson.

Asbenson has been exchanging texts with a 14-year-old girl who escaped from an abductor. The police are actively searching for the man and believe he has killed others. The girl thinks she sees her abductor everywhere. Asbenson understands because that happened to her as well.

Asbenson texted: “It’s the PTSD. Do you have a therapist?”

“I asked her if she felt safe. I encouraged her to love and not blame herself. I recommended that she get a service dog. A dog is not only comforting, it barks and can let you know if there’s someone out there.”

Asbenson has two dogs.

THE STORY

At eight years old, Asbenson knew she had a story to tell and that some day it would be a movie or a book. With a vivid imagination, she could see the moments of her life like scenes on a screen.

“I could see myself belittled and abuse. A poor young girl chasing after her disabled brother was horrible, but in my mind it was going to be beautiful and meaningful one day,” said Asbenson. “People need to know the circumstances of how I grew up and how it enabled my kidnapping.”

Asbenson admits to being shy and that she has trust issues. She is careful whom she lets into her life.

WARRIORS & ROCK STARS

On the inside of Asbenson’s forearm where there are scars from self-inflicted wounds, she has tattooed “Warrior.”

On the inside of Asbenson’s forearm where there are scars from self-inflicted wounds, she has tattooed “Warrior.”

“At the end of writing my story, I fell in love with myself. I realized the mental illnesses I have are okay. PTSD is expected,” said Asbenson. “People started to call me a warrior and that made me feel proud. I believe that everybody who has gotten through something difficult is a survivor. If you fight to better yourself and share your story to help others, you earn a new badge – you are a warrior.”

Asbenson plans to tattoo “Rock Star” on the inside of her other arm, which is another moniker people have bestowed on her.

“I like it, because when a warrior flips all the ugliness into something really amazing, then you become a rock star!” said Asbenson.

Asbenson was waiting for someone else to tell her story and realized she had to do it herself.

SKILLSET

“No one can tell my story the way I can,” Asbenson said. “It was really, really hard and I had to relive and feel it all over again. I would get revelations and see how the pieces fit together. I didn’t know my entire story until I finished writing it.”

With the book’s release, Asbenson is excited.

“I’m overwhelmed, but that’s a good thing,” said Asbenson. “Being under-whelmed is boring.”

Without a doubt, Asbenson has been changed by the events in her life. Her difficult childhood made her susceptible to being victimized, while her young life also provided her the practical skillset to survive.

“If this didn’t happen, I’m not sure the kind of person I would have become,” Asbenson said. “I turned it around and made it into something that I can be proud of. I learned to love myself. I’m okay with what happened and I forgive everyone. And that sets me free. I want to be myself and live fully.”

Asbenson has made her message about personal empowerment.

SOUL SURVIVOR

“If you’re looking for someone else to fill your soul, it’s not going to happen,” said Asbenson. “It has to start with you. You have to do what makes you happy and gives you joy. You have to decide who you want to be, who you’re going to become. If you’re true to yourself, really love yourself, it will show.”

Asbenson is motivated by those reading her story.

“I’m inspired,” said Asbenson. “That’s what’s real for me. I’m proud of what I’ve become and I love myself. It was here, in my tree house, that I told my story and reclaimed my life.”

Jennifer Asbenson’s identity is no longer just the girl who escaped a serial killer, but the girl in the tree house.

Jennifer Asbenson will be signing copies of her book The Girl in the Treehouse at Big Rock Pub in Indio, Thursday, February 7, 4:00- 7:00pm