Palm Springs’ flip side: Mobsters, Gamblers and Section 14

Frank Bogert was the resort town’s mayor in transitional early ’60s, but Judge Hilton McCabe reigned as its ‘Little White Father’

Read part one of “The Flip Side of Utopia” at CoachellaValleyWeekly.com/the-flip-side-of-utopia-part-1.

By Bruce Fessier

Dwight Eisenhower, Frank Sinatra, Bob Hope and Dinah Shore were the Mt. Rushmore of mid-century modern Palm Springs. The faces of the desert utopia.

But Ray Ryan, Judge Hilton McCabe and Frank Bogert were key to Palm Springs’ generational changes of 1962-63.

Ryan, born in Watertown, Wisconsin in 1904, had been a Palm Springs force since 1952 when he and investors bought the El Mirador Hotel, at the site of today’s Desert Regional Medical Center. He became vice president, giving him time to enjoy the hotel action and play high-stakes poker at the nearby Sunset Tower Apartment Hotel with Zeppo Marx, youngest of the Marx Bros., and George Cameron Jr., owner of The Desert Sun and KDES radio.

But in 1957, Tony “Big Tuna” Accardo handed the reins of the Chicago Outfit to Sam Giancana and began wintering in Palm Springs. Bogert was managing the El Mirador, and he told Herb Marynell, co-author of the Ryan tome, “Mob Murder of America’s Greatest Gambler,” he drove Accardo around Palm Springs, looking to buy property.

Many mobsters liked vacationing at the El Mirador, Marynell said, including Johnny Roselli.

Ryan was not a Mafia member, said Clayton Taylor, who opened the FBI’s Palm Springs office in August 1961. But he was affected by a 1957 FBI mob crackdown when G-men raided a bookmaking operation north of his family home in Evansville, Indiana. They found evidence of Ryan placing large bets with a bookie they arrested. Zeppo was forced to testify to a grand jury there. Ryan would have been called if he hadn’t been hopscotching around the world.

Roberta Linn, who Ryan helped become Desert Circus queen in 1955, accompanied him on several trips while his wife stayed in Evansville.

“I remember he came back from Iran; he was making an oil deal over there,” Linn told me at her Rancho Mirage home. “I was working at the Copacabana (in New York). He got front row seats for ‘My Fair Lady’ and he fell asleep! He had jet lag and was snoring in the middle of the show!

“The last trip I remember as a really big trip was the one to Havana. All the boys were in from all over. It was right after that that (Fidel) Castro took it away.”

Ryan and his movie star pal, William Holden, started the Mt. Kenya Safari Club in Eastern Africa with Ryan’s Swiss banker, Carl Hirschmann, in 1959. They converted a modest 100-acre hunting lodge into an exotic safari club. Their British friend and Kenya resident, the Duke of Manchester, helped sign Winston Churchill and Prince Philip as charter members. Ryan and Holden got Clark Gable, Walt Disney, John Wayne, and Sen. Lyndon Johnson, among others. All gained opportunities to shoot elephants, zebras, giraffes, and rhinoceroses.

Ryan felt safe enough in Palm Springs to find partners to launch a business empire. He co-founded Bermuda Dunes Country Club in 1958 and the North Shore Beach & Yacht Club at the Salton Sea in ’59. He and Bogert started a Palm Springs Capital Company to fund a $15 million golf resort, which collapsed after Ryan’s development partner died in a car crash. He owned a majority of The Villager magazine from 1955 to 1959, establishing Bogert as vice president. He sold it to Palm Springs Life when that magazine perpetuated The Villager’s romanticized view of Palm Springs as the “official organ of the country clubs.”

The Indiana grand jury disbanded in late 1959, and Ryan kept spending money in Palm Springs. He bought out his El Mirador investors, upgraded the hotel and developed the now-vacant Palm Springs Shopping Mall with Seeterra, Inc.

Accardo’s desire to make Palm Springs a safe haven might have made Ryan feel secure being high-profile.

“This was an off-limits area,” Linn said. “There was no boom-boom that was supposed to go on in this town. They came down here to get away and have a good time without any political stuff.”

But the FBI investigated Ryan when he sought investment money from Jimmy Hoffa’s Teamsters Pension Fund.

“I first met him in 1959 when I came here on special (assignment),” said Taylor, who had been based in the FBI’s L.A. office. “The Teamsters were getting kickbacks on the loans, so I came to talk to Ray Ryan and Frank Hayden, his general manager. The loan didn’t go through because the Teamsters found out we were investigating it before it even got off the ground. So there was a little animosity on their part toward me when I transferred and opened the office here.”

Ryan’s fleecing of gambler Nick “The Greek” Dandolos in a 1949 poker game also engendered rancor towards Ryan. Linn said he ended their relationship in ’59 over concern for her safety.

“They were really after him,” she recalled. “He said, ‘You cannot be around me anymore, Honey.’ When he went to the bathroom, he had a bodyguard.”

Ryan tried to pay off Dandolos after he accused Ryan of cheating. That emboldened Giancana lieutenant Marshal Caifano to test Accardo’s “no boom-boom” edict, taking a thug with him to the El Mirador and offering Ryan “protection.” Ryan fled town in search of his own protection.

“I got in on that,” Taylor told me in 2014. “What happened was, they approached him here in Palm Springs, trying to get a shakedown for money. I think they approached him at (El Mirador’s) barbershop. He went directly to Las Vegas. The hoodlums rented a plane and flew over and approached him at the Desert Inn. They tried to shake him down again, but he, being Ryan, called the FBI and they were arrested.”

“They wanted to extort $60,000 a year from him,” said Betsy Duncan. “So he went to the FBI, which he probably shouldn’t have done. There was a (hit) put out on him. I called a friend in Vegas, who was a friend also of Ray’s. I said, ‘Can’t you do something about this? Can you intervene with the guys?’ He came back and said, ‘He’s got a 10-year.’ Ten years to go get him. I even asked Johnny Roselli about that. He said, ‘Ah, he’s all right.’ I said, ‘Well, he’s not all right when (a mobster) puts out that he’s going to kill somebody.’ He said nothing.”

Caifano was convicted of extortion in 1964. He began serving two concurrent sentences in 1966. He got out early in 1972 and possibly exacted revenge in ’77. Ryan flipped his ignition in an Evansville parking lot and a bomb went off. No one was ever arrested for the murder.

“I was in the hospital in Northridge when they blew the car up,” said Linn. “I get tears in my eyes thinking about it. It was just a terrible thing.”

Mistreating the Indians

Another historic 1963 event was the opening of the Palm Springs Spa Hotel on a sacred Cahuilla hot springs, called Sek-hi, on the Agua Caliente reservation.

It was made possible in 1959 when President Eisenhower signed two pieces of legislation — the Long-Term Leasing Act and the Equalization Act — just hours before departing for a Palm Springs golf vacation, where he had to land at the airport on Agua Caliente-owned property.

The Long-Term Leasing Act enabled Chicago developer Samuel Banowit to sign America’s first 99-year lease of Indian land to qualify for financing. Before 1956, tribes had only been allowed to lease parcels for up to five years with no options for renewals.

The Equalization Act basically made every Agua Caliente parcel equal in value, but it came with a provision placing the tribe under a California Conservatorship Law. That meant, if a Riverside County Superior Court judge felt a tribal member needed help handling his or her affairs, the member’s property could be put under the control of a conservator, who could charge for his services.

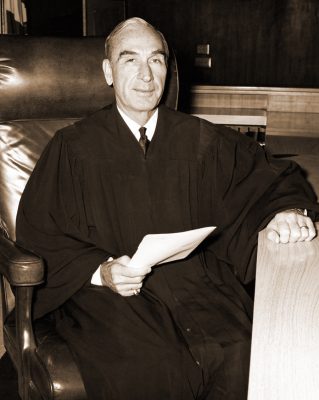

Hilton McCabe, a former board chairman of the Palm Springs Unified School District and board president of the Palm Springs Desert Museum, was the main judge deciding who needed help. Ed Ainsworth, a Los Angeles Times editor who lived in the Coachella Valley, called him “the Little White Father of the Indians of Palm Springs” in his 1965 book, “Golden Checkerboard.”

Vyola Ortner, born and raised in Palm Springs by an Agua Caliente mother and a German-American father, told me she wasn’t required to have a conservator. She was raising her family in Downey when she was asked to be the Tribal Council’s vice chair in 1952. She said she filled out a document saying she didn’t want a conservator and didn’t get one.

But most tribal members had conservators, including Joe Patencio, a ceremonial dancer and entrepreneurial pioneer, and Richard Milanovich, who served in the Army from 1960-’63 and became a national leader in tribal affairs.

McCabe, who died in 1988 at age 81, took credit for making the Agua Caliente a “wealthy people” with his leadership. Working with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Superior Court judges appointed civic leaders as conservators, including Bogert while he was mayor, Police Chief Gus Kettmann, Black developer Lawrence Crossley and McCabe himself.

The Desert Sun called McCabe one of the desert’s “most respected citizens” in 1961. But in 1963, the year Martin Luther King Jr. had a dream about seeing his children “not be judged by the color of their skin,” an anthropologist cried foul.

“The conservator issue was itself inherently abusive,” Lowell Bean told me in 2013. “I was working for the Desert Museum (now the Palm Sprins Art Museum) and they wanted to raise money. So the judge decided he would instruct all the conservators to contribute to the funding of the museum since there was a Cahuilla Indian (exhibit). I was very young, and I thought of that as abusive – deciding what to do with someone else’s money without their permission. So I went to Eileen Miguel, who was chairman, and Eileen raised absolute hell. She went charging into his office and really let him have it. I was fired the next day because I had ratted on the judge. The judge was a big man in this town.”

The program continued through 1969 when Congress amended the Equalization Act to prohibit “further abuse of Native Americans.” Interior Secretary Stewart Udall called the fees tribal members had to pay conservators, guardians and attorneys “unconscionable.”

Black tenants found it especially hard to find new housing after their evictions. Deeds going back to the 1930s expressly forbade real estate buyers from selling, renting or even letting Blacks occupy white-owned land. Redlining policies enacted in 1934 by the Federal Housing Authority to identify U.S. neighborhoods deemed “hazardous” for real estate investment inhibited banks from giving home loans to groups of African Americans.

Section 14 diaspora

The Palm Springs’ city council had long debated what to do with Section 14 occupants, many of whom were domestic workers for the stars.

The city claimed in the early ’50s it had to evict them because their dwellings on seemingly sovereign land didn’t meet state of California standards. Councilman Jerry Nathanson argued unsuccessfully for letting them rent homes in a veterans housing tract.

“These people were ordered from their homes by city, county and state authorities,” he said at a June 1951 city council meeting. “Their homes were condemned as unfit for human habitation. But they were the only homes they could occupy.”

The African American residents formed a Palm Springs chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People that year. When regional NAACP leaders threatened a lawsuit, the city postponed eviction proceedings against five families.

But Black residents lived in fear of losing their homes. Cora Crawford, who died in 1991 after earning accolades for her work in early childhood education as director of the Palm Springs Child Development Center, said that’s why she moved to an off-reservation housing tract that Crossley said he developed “for my people.”

“We moved because I had these little babies and they were talking about bulldozing the houses down,” Crawford told Palm Springs Historical Society director of education and associate curator Renee Brown for an oral history. “I couldn’t sleep thinking about them coming in the night. I was even dreaming they were pushing the house down.”

Charles Jordan, a 1956 Palm Springs High School graduate who became the town’s assistant to the city manager in 1968 and Portland’s first Black city council member in 1974, said the impoverished residents of Section 14 lived in relative racial harmony. But his family had to move to Banning after the urban renewal.

“We lived in little shanty trailers,” Jordan said in a 2001 Oregon Historical Society interview before his 2014 death. “They had common facilities in the middle of the reservation, so everyone came to those showers and restrooms there. When I graduated, urban renewal came on the scene. They had to get us off the land and — no exaggeration — they literally gave us short notice. If you were not out of there by that time, they came and took your possessions and set them outside. They burned the trailers and the shanties that we lived in.”

Joe Patencio’s former Section 14 home was burned in September 1956 by police officers described by The Desert Sun as “avid supporters of the clean-up campaign.”

“New legislation has put the situation into the hands of the governing city and its police department,” the paper reported. “Now a simple procedure can rid the area of the attractive nuisances.”

Cowboy mayor on the scene

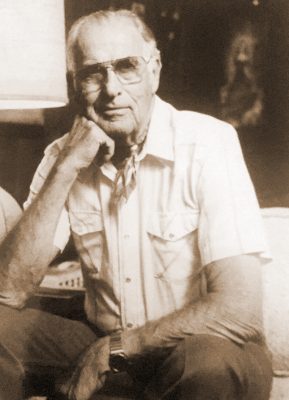

Bogert, who died in 2009 at age 99, became mayor in 1958 after a decade of trying to develop private projects, including a dude ranch and a quarter horse racetrack in Rancho Mirage.

He grew up in Mesa, Colorado, which may be where he learned to like unique characters. The bank-robbing outlaw Butch Cassidy worked as a ranch hand there and Bogert told me his neighbors found him to be “a real nice fellow.”

His family moved to Wrightwood in the San Gabriel Mountains, and Frank rode into Palm Springs on horseback in 1927, delivering 60 horses to a stable at age 17.

But he wasn’t just a cowboy. He went to UCLA with plans to study anthropology. He instead majored in zoology, delving into indigenous culture as a passion. He was fluent in Spanish and especially fascinated by Mexican native culture. His second wife, Negie, was born in Mexico.

His home-spun humor, honed in an L.A. acting class with fellow student Lucille Ball, served him well as a rodeo announcer and speaker on the local charity circuit. His service as a World War II Navy officer reinforced his sense of public duty and chain of command.

But he had an open mind about gambling, especially after becoming manager of Thunderbird Country Club on the site of his old dude ranch. High stakes gamblers filled its card room and security guards protected their privacy. Meanwhile, placing bets beyond the country club gates could get a guy arrested.

The cowboy businessman’s complex characteristics endeared Bogert to individuals ranging from George Allardice, an out-gay society singer and editor of the desert’s Platinum Registry, to Andy the Donkey Man. His diverse friends included Crossley, Milanovich, Father of Chicano music Lalo Guerrero, and Rabbi Joseph Hurwitz.

Palm Springs was systemically racist, anti-Semitic, and homophobic. LGBTQ+ nightclubs, like gambling clubs, rock music and the Black History Parade, had to start outside of Palm Springs’ city limits. Hurwitz and the African American Rev. Jeff Rollins both arrived in 1958 with missions to end anti-Semitism and racism, respectively.

But, in the rarified circles Bogert traversed with mobsters, stars and the super-rich, lanes overlapped and barriers were transcended.

“We never thought about what was gay and what wasn’t,” Allardice told me six years before his 2001 death. “We never thought about who the gangsters were. We just thought they were nice people and didn’t worry about it.”

Local Indian lore and folk remedies also enchanted Bogert in pre-war Palm Springs.

“In those days, the Indians lived on Section 14,” Bogert told me. “One day, I was riding through the area and stopped to talk to an old gal I always talked to, and I couldn’t talk. She said, ‘What’s the matter?’ I said, ‘I’ve got a sore throat.’ She said, ‘You go finish your riding and when you come back through here, I’ll have some medicine for you.’ She gave me a gourd about that thick full of the most horrible-tasting shit you ever had in your whole life, and she made me drink the whole thing. By the time I got to the stable, I could talk. I never did find out what it was. They had a lot of cures that we don’t even begin to know about.”

How Blacks were diverted north

Bogert said the Section 14 urban renewal movement began when Palm Springs was incorporating in 1938 and business leaders were hatching an image for it.

“The business and hotel people downtown felt they had a problem with these poor folks living in their own neighborhood,” Bogert told me. “That’s when the movement started to find a place where they could be out of town, away from that area. That’s when the community started in the Black area to the north.”

During the first week of 1961, Building Inspector Jack Sanders told The Desert Sun 44 homes had been “cleared” from Section 14 since February 1956 and another half-dozen were being condemned. That forced minority residents to double or triple up in the remaining homes, Sanders said, “because there just isn’t anywhere else they can go.”

The Desert Sun credited Bogert with “working steadily to get private money to build a low-cost rental-unit project for these people, but the location has been the big problem.” It quoted him as saying, “If it is too far from downtown, they can’t get into town.”

But Arwen Nuttal, a writer-editor for American Indian, the magazine of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, wrote in 2019 that the city manipulated the tribe into conforming to its vision of Section 14.

“City leaders could not acquire tribally-owned land outright, so they attempted to restrict building, zoning and leasing on Section 14 as a means to control the area,” Nuttal wrote. “In the 1940s and early 1950s, the city of Palm Springs proposed three master plans to develop Section 14. But it never implemented them. Instead, it argued that tenants had to either bring their homes up to code or face eviction.

“The tribe had made earlier requests to the city of Palm Springs to provide utilities to Section 14 residents, but the city refused. It claimed residents did not pay property taxes on reservation land. However, Loren Miller Jr., assistant attorney general for the State of California, conducted an investigation in 1968 and found tribal members did pay taxes.”

After 1959, the city could evict Section 14 residents by saying it was adhering to the will of tribal members by cooperating with their conservators, who, Nuttal said, favored “terminating land leases and serving tenants notices of eviction.”

In February 1962, the city council asked the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Association of Conservators and Guardians to “cooperate with the City” to clean up “demolition of substandard dwellings” in Section 14. But it didn’t request cooperation from the Tribal Council or its tenants.

The abatement program was scheduled to conclude in June 1966. But in February 1967, the council and Bureau of Indian Affairs contracted to further demolish and burn structures and remove debris from Section 14. The Tribal Council wasn’t cited as a party in that agreement.

A key to a current debate between the Section 14 Survivors group seeking city reparations, and opponents saying Section 14 residents were legally served eviction notices, is whether the homes were destroyed within the properly prescribed time the eviction notices were received by tenants.

Section 14 “survivors” recall Bogert showing up at their doorsteps and exhorting them to evacuate because fire trucks were coming. Sometimes, they say, heightened emotions elevated into confrontations.

Nuttal wrote, “Miller found during his investigation that, ‘The City, acting upon the [eviction] permit, would burn down or destroy the dwelling in question any time it had received the permit without actually checking to see whether the time prescribed in the eviction notice had expired.’”

Miller’s investigation included his now-famous characterization that the displacement of Section 14 residents was “a city-engineered holocaust.” He cited many tenants saying they lost belongings when their homes were razed. Miller concluded, “The city of Palm Springs not only disregarded the residents of Section 14 as property owners, taxpayers and voters; Palm Springs ignored that the residents of Section 14 were human beings.”

Bogert left the city council to start a PR business after unsuccessfully arguing for low-cost housing for displaced Section 14 residents. He traveled to Washington D.C. with a contingent including Beverly Hills developer Joe Bolker and the Rev. Rollins of the First Baptist Church of Palm Springs in 1967, asking the FHA for 80 percent funding for a North Palm Springs housing tract. The other 20 percent was to come from the city with sponsorships by Rollins’ First Baptist Church and the Los Angeles Psychological-Social Center.

Low-cost housing was needed, they told the FHA, because a city-led “Section 14 cleanup” had forced local workers (primarily Blacks) to move to Banning and Garnet, where redlining policies were less prohibitive. A May 23, 1967 Desert Sun caption said, “Bogert has been pushing for a low-cost housing development for 10 years.”

But that December, the city council majority under Mayor Howard Wiefels killed Bolker’s 100-unit low-cost housing proposal, calling it a “federal rent supplement plan.”

Bogert, meanwhile, still wanted to get paid for his conservatorship work.

He released Tribal Council member Edmund Peter Siva from his conservatorship in 1963. But that release order required Siva to make spousal and child-support payments, and to pay Bogert for helping Siva craft a long-term lease. In December 1966, the Superior Court said Siva was delinquent on his family support and his $6,000 debt to Bogert. In October 1967, Bogert and Siva’s ex-wife and his son’s guardian, James Hollowell, filed a Superior Court petition to declare Siva incompetent and to re-appoint a conservator for his estate.

The next April, the Department of the Interior recommended abolishing the conservator-guardian program due to abusive practices by some conservators, guardians and attorneys, including Hollowell. Siva was cited as a tribal spokesman applauding the Interior Department report.

“What we originally wanted when the land equalization was passed were guardians for some of the minors who were being milked by their parents,” he told The Desert Sun. “We did not want guardians or conservators for adults, but that is what we got.”

Generalizing about episodes from 60-year-old pieces of information is as problematic as drawing conclusions about Bogert from a statue. A Mexican sculptor’s depiction of the man known as “El Grandiote” in Mexico may now be viewed as a symbol of Palm Springs’ troubled past. But it can’t explain Bogert’s complexities or the complicated realities of Section 14 residents.

“I don’t know who were the main players,” the late Section 14 resident, Ivory Murrell, said in a 2011 Palm Springs Historical Society interview. “But I really felt that the mayor, Bogert, could have done better about what was happening to us. Some of the people never got the stuff out of their houses. They pushed them down. If they told you they was coming in and your stuff wasn’t out there, they just pushed you down.”

Bruce Fessier is a veteran Rancho Mirage-based journalist. Contact him at jbfess@gmail.com, facebook.com/bruce.fessier, instagram.com/bfessier/ or twitter.com/BruceFessier.